What Religion Did The Ottomans Hate? Exploring A Diverse Historical Empire

Many folks wonder, "What religion did the Ottomans hate?" It's a question that, you know, comes up a lot when people think about history. People often imagine empires as places where one group rules over others with a very firm hand, sometimes even with strong dislike for different beliefs. But the truth about the Ottoman Empire and its many different faiths is, in some respects, more layered than a simple answer might suggest. We're going to look at what historical records and research actually show us about this rather fascinating period.

The Ottoman Empire, for nearly all of its 600 years, was officially an Islamic caliphate, ruled by a sultan, like Mehmed V, for instance. Yet, it also held within its vast borders Christians, Jews, and other religious minorities, a fact that, you know, might surprise some. This arrangement, in a way, shaped much of its political and religious story across early modern Europe and beyond.

So, we'll go through what we know about how the Ottomans handled different faiths. We'll explore if "hate" is the right word to describe their approach to other religions, or if something else, something perhaps more practical or, you know, even tolerant, was at play. This piece will help shed some light on a very important part of world history.

Table of Contents

- The Ottoman Empire: An Islamic Caliphate with Diverse Peoples

- Was There "Hate"? Examining Historical Relationships

- Religious Observance and Education in the Empire's Context

- Beyond Simple Narratives: The Nuance of Ottoman History

- Frequently Asked Questions About Ottoman Religious Relations

The Ottoman Empire: An Islamic Caliphate with Diverse Peoples

The Ottoman Empire, for centuries, was a massive entity, truly a very large one, that spanned continents. It was, as a matter of fact, an Islamic caliphate, with a sultan at its head, like Mehmed V. Yet, this powerful state was not, you know, solely Muslim. It was home to many different groups of people, including Christians and Jews, and other religious minorities, too it's almost. This mix of faiths was a very real part of the empire's fabric, something that shaped its character.

Understanding Ottoman Rule and Religion

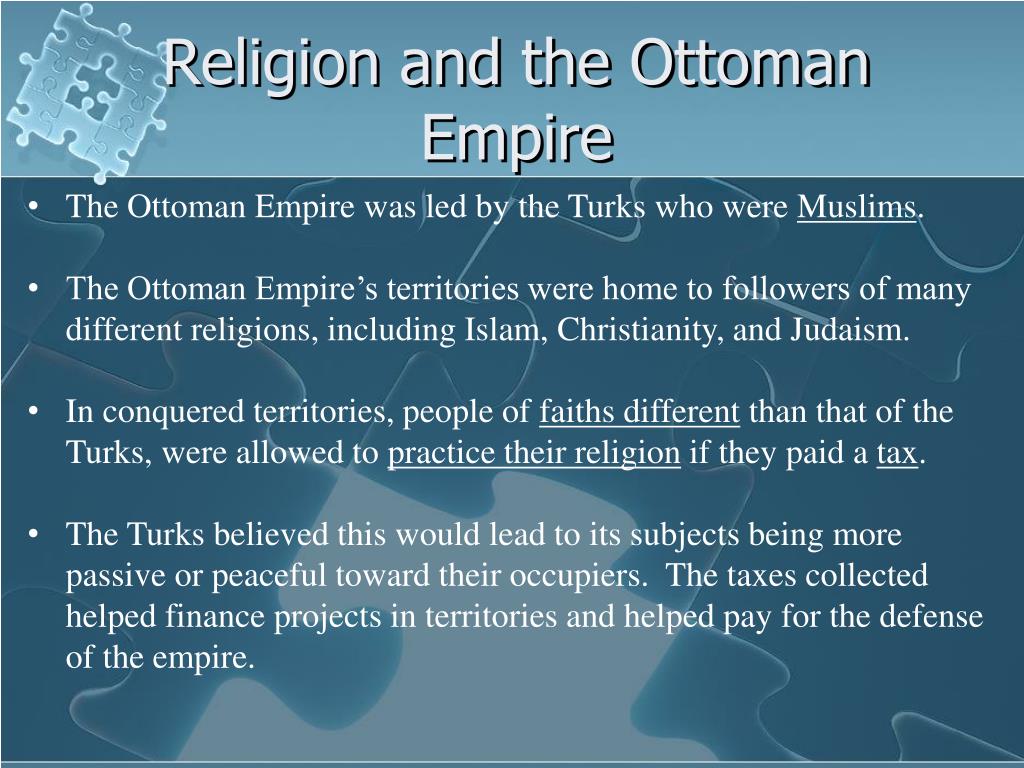

The core of Ottoman rule was based on Islamic principles, obviously, but its governance had to account for its vast, diverse population. The rulers, you know, understood that they governed people with different customs and different ways of worship. This meant that, basically, a system was needed to manage these differences without constant conflict. The empire's expansion, for instance, brought many new groups under its control, each with their own religious practices.

This situation was, in some respects, quite different from what some European observers might have expected or even, you know, hoped for. The rise of the Ottoman Empire and its reach, for example, were often viewed with a bit of apprehension from European lands. People in Europe, it seems, wondered how the Ottomans would shape the political and religious history of early modern Europe, and that, you know, was a big question.

The Millet System: A Framework for Coexistence

To manage its varied population, the Ottoman Empire used a system known as the millet system. This system, in a way, allowed religious communities, or "millets," to govern themselves under their own religious laws. Christian and Jewish communities, for instance, could maintain their own schools, courts, and even, you know, collect their own taxes. This was a rather practical approach to rule, allowing for a degree of self-governance for non-Muslims, which, arguably, helped keep the peace.

This system meant that, while the sultan was the ultimate authority, the daily lives of Christians and Jews were largely handled by their own religious leaders. It's important to note that, for example, they were still subjects of the empire and paid specific taxes, like the jizya, which was a tax for non-Muslims. However, this structure meant that, basically, the empire did not, as a rule, seek to eliminate or force conversion upon these groups. It was a method for, you know, managing a diverse population over a very long time.

Was There "Hate"? Examining Historical Relationships

The question of whether the Ottomans "hated" a particular religion is, you know, a very strong claim. Historical accounts, including those from our text, suggest a more complex reality than simple hatred. The empire, after all, incorporated these groups rather than, you know, trying to eradicate them. This doesn't mean relations were always smooth, but it does mean that a policy of outright hatred towards a specific faith was not the prevailing approach, at least not in the sense of trying to wipe it out.

Perceptions from Europe

European observers, as a matter of fact, often saw the Ottoman Empire through a lens of fear and religious difference. There was, for example, a general concern about the expansion of an Islamic power into Christian lands. Interestingly, our text mentions a letter where Pope Pius II assured the sultan that he did not hate him, stating that his lord bade him love his enemies and pray for his persecutors. This, you know, suggests that the perception of hatred might have been more on the European side, a feeling of being persecuted, rather than a stated Ottoman policy of hating a religion.

The Pope's words imply that there was a common belief, perhaps a "delusion" as he called it, that he, or Christians generally, harbored hate. This particular exchange, you know, points to the complex interplay of religious and political tensions between the Ottoman Empire and European states. It wasn't, arguably, about the Ottomans hating Christianity as a faith, but rather about geopolitical rivalry and, you know, clashes over territory and influence.

Treatment of Non-Muslims

While non-Muslims in the Ottoman Empire were not equal to Muslims in all respects, their lives were, generally, protected under the millet system. They had, for instance, certain rights and responsibilities. They could practice their faith, maintain their places of worship, and conduct their community affairs. This was, in a way, a pragmatic approach for an empire that needed the skills and contributions of all its peoples.

There were, of course, periods of conflict and instances of harsh treatment, but these were often tied to specific political events or rebellions, not, you know, a blanket policy of religious hatred. The empire's longevity, in short, relied on its ability to manage its diverse population, which meant, basically, a degree of accommodation rather than constant persecution based purely on religious identity. This is, you know, a key point to remember when thinking about the Ottomans.

Religious Observance and Education in the Empire's Context

Our text talks about how religion is measured in surveys and how, you know, knowledge about a religion can affect views of its adherents. This idea, while applied to modern contexts like the U.S. religious landscape, can, in a way, offer a bit of insight into the Ottoman experience too. The empire, after all, had many different religious groups living side by side, so some level of, you know, interaction and understanding was inevitable.

Education and Religious Knowledge

Within the Ottoman Empire, religious education was, naturally, very important for each community. Muslim scholars studied Islamic texts, while Christian and Jewish communities had their own schools and places of learning. Our text mentions that those who are most knowledgeable about a religion, even if they aren't members, tend to rate the religion's adherents most favorably. This suggests that, you know, understanding can lead to more positive views.

While we don't have direct survey data from the Ottoman period, it's fair to say that, in a society where different faiths lived together, a certain level of practical knowledge about each other's ways of life would have been, arguably, necessary. This might have, in some respects, prevented widespread, uninformed hatred, as people, you know, had some direct experience with their neighbors of different faiths.

Shifting Religious Landscapes

The idea of a changing religious landscape is also something our text touches upon, specifically regarding the U.S. population. While the Ottoman Empire's religious composition was relatively stable for centuries, the very presence of multiple faiths meant that, you know, the religious "landscape" was always diverse. The empire had to adapt to this reality, ensuring that its governance could accommodate these differences over time.

The concept of religious shifts, even if gradual, was a constant feature of the empire's long history. The fact that Christians and Jews remained distinct communities for hundreds of years under Ottoman rule shows that, basically, their religious identities were preserved. This is a very different outcome than if a policy of outright hatred and forced conversion had been, you know, consistently applied. Learn more about religious diversity on our site.

Beyond Simple Narratives: The Nuance of Ottoman History

When we ask "What religion did the Ottomans hate?", we're looking for a simple answer to a very complex historical situation. The reality is, you know, much more nuanced. The Ottoman Empire was a powerful state that expanded through conquest, but its long-term survival depended on managing its diverse populations, not simply hating them. It was, in a way, a pragmatic empire, focused on administration and maintaining control.

The empire's relationship with various religions involved periods of cooperation, taxation, and sometimes, of course, conflict. It was not, you know, a utopia of perfect harmony, but neither was it a state driven by pure religious animosity towards any single faith. Understanding this requires looking at the historical context, rather than applying modern ideas of "hate" to a very different time and place. For instance, you can find more information about the historical context of the Ottoman Empire on reputable academic sites, like this one: Britannica's Ottoman Empire overview.

The way the Ottomans shaped the political and religious history of early modern Europe was, arguably, through their very existence as a multi-religious empire, rather than through a policy of religious hatred. They were a major power that, you know, interacted with European states in many ways, often in competition, but their internal religious policies were, basically, designed for stability. You can also link to this page for more historical context.

Frequently Asked Questions About Ottoman Religious Relations

Did the Ottomans tolerate other religions?

The Ottomans, in a way, showed a practical tolerance towards other religions, particularly Christianity and Judaism. They did not, you know, force widespread conversions and allowed these communities to largely govern their own internal affairs under the millet system. This was, basically, a pragmatic approach to managing a vast, diverse empire, allowing for a degree of religious freedom within certain bounds.

How did the Ottoman Empire treat Christians?

Christians in the Ottoman Empire were, generally, considered "People of the Book" and were protected as religious minorities. They had to pay a special tax, the jizya, and faced certain limitations compared to Muslims, but they could practice their faith, maintain churches, and live according to their own community rules. Treatment varied over time and place, but, you know, their existence as distinct communities was largely preserved.

What was the official religion of the Ottoman Empire?

The official religion of the Ottoman Empire was, very clearly, Islam. The empire was an Islamic caliphate, and the sultan was, in some respects, considered the caliph, the leader of the Muslim world. This meant that Islamic law and principles guided the state's highest functions, even though it governed a population that, you know, included many non-Muslims.

PPT - The Ottoman Empire PowerPoint Presentation, free download - ID:5832513

HISTORY: The Ottoman’s dark and oppressive role in the Arab lands – The Milli Chronicle

What was the religion of the Ottoman Empire? What impact did it have on Ottoman literature? - iNEWS