Does The IRS Forgive Tax Debt From A Deceased Person? What Families Need To Know

When a loved one passes away, the grief can be overwhelming, and dealing with their affairs often adds a heavy burden. Among the many questions that surface, a really significant one for many families is whether the IRS just wipes away any tax debt the person might have owed. It's a common worry, and frankly, a very important one to address during such a sensitive time.

So, you might be wondering, what happens to those unpaid taxes? Does the debt simply vanish, or do family members suddenly become responsible? This question, as a matter of fact, comes up quite a bit. It’s a situation that can feel a bit confusing, especially when you're already going through so much. Understanding the process can help bring some peace of mind and, perhaps, guide your next steps.

This article will shed some light on how the IRS handles tax obligations when someone is no longer with us. We'll look at the general rules, what exceptions might exist, and what family members or estate representatives typically need to do. It's all about getting a clearer picture, so you can handle things properly, you know, without extra stress.

Here's a quick look at what we'll cover:

- What Happens to Tax Debt When Someone Dies?

- Who is Responsible for a Deceased Person's Tax Debt?

- Types of Tax Debt and Their Impact

- The Role of the Estate in Paying Tax Debt

- When an Estate is Insolvent

- Spousal Relief: A Potential Lifeline

- Offers in Compromise (OIC) for Deceased Taxpayers

- Practical Steps for Executors and Family Members

- Seeking Professional Help

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Happens to Tax Debt When Someone Dies?

It’s a natural thought to wonder if debts, especially tax debts, just disappear when a person passes on. However, the IRS, generally speaking, doesn't simply forgive tax debt because someone has died. The tax obligations usually don't just vanish into thin air. Instead, they become a responsibility of the deceased person's estate.

An estate, in simple terms, is everything the person owned at the time of their passing. This includes their money, property, investments, and other assets. Before any heirs can receive what's left, the estate must settle all outstanding debts, and that includes any taxes owed to the IRS. So, in a way, the debt lives on, but it's tied to the assets, not directly to the family members themselves, which is pretty important to know.

The process of settling an estate is called probate, and it can be a rather involved legal process. During probate, a court-appointed individual, often called an executor or personal representative, gathers all the assets, pays off legitimate debts, and then distributes what remains according to the will or state law. Tax debt is, in fact, a priority debt, meaning it often gets paid before other creditors or beneficiaries. This is why, you know, it's such a critical part of the whole process.

The IRS's Claim on the Estate

The IRS has a claim against the deceased person's assets. This means they are a creditor, just like a bank or a credit card company. However, the IRS's claim often takes precedence over many other types of claims. This is why, frankly, it’s so vital to address any potential tax debt early on. The federal government, you see, usually gets paid first from the estate's funds.

If there are enough assets in the estate to cover the tax debt, then the debt is paid from those assets. It's a fairly straightforward process in that scenario. The executor simply uses the estate's money to pay the IRS, and then, you know, they move on to other obligations. This is the ideal outcome, as it means the debt is handled without further complications.

However, what happens if the estate doesn't have enough money or assets to cover the debt? This is where things can get a bit more complicated, and it's a situation that, apparently, causes a lot of worry for families. We'll explore that scenario a little more later, but the general rule is that the debt doesn't just disappear; it attempts to be collected from the available resources.

Who is Responsible for a Deceased Person's Tax Debt?

This is a question that, quite frankly, causes a lot of anxiety for grieving families. The good news is that, in most situations, family members are not personally responsible for a deceased person's tax debt. The responsibility typically falls on the deceased person's estate. This is a key distinction, and it's something that, you know, can really help alleviate some fears.

The executor or personal representative of the estate is the person legally tasked with handling the deceased's financial affairs, including paying any taxes owed. Their job is to manage the estate's assets, pay off debts, and distribute the remaining property to the rightful heirs. They act on behalf of the estate, not in their personal capacity, when it comes to these financial obligations. So, it's the estate's money, not the executor's personal funds, that are used.

There are, however, some specific situations where a surviving family member might become responsible for tax debt. These are generally exceptions to the rule and include things like joint tax liabilities, certain types of transfers, or if the family member was involved in fraudulent activity related to the taxes. It's not common for innocent family members to suddenly inherit the debt, but it's important to be aware of these potential scenarios, just in case.

Executor's Role and Potential Liability

The executor has a very important role, and with that comes certain responsibilities. They are legally obligated to ensure that all valid debts, including tax debts, are paid before distributing assets to beneficiaries. If an executor distributes assets to heirs before paying the IRS, and there isn't enough left to cover the tax debt, they could, in some cases, become personally liable for that unpaid amount. This is why, you know, it's so important for executors to be very careful and follow all legal procedures.

This personal liability for an executor is not automatic, mind you. It usually arises if they acted negligently or fraudulently, or if they knew about the tax debt and still prioritized other payments or distributions. For example, if they knowingly paid a beneficiary before paying the IRS, and the estate then ran out of money, they might be on the hook. This is why, for example, getting professional advice is often a very good idea for executors.

To avoid personal liability, an executor should always prioritize paying the deceased's debts, especially federal taxes, before distributing any assets. They should also keep meticulous records of all financial transactions within the estate. This due diligence protects both the executor and the estate. It's a pretty serious responsibility, actually, and one that requires careful attention.

Types of Tax Debt and Their Impact

When we talk about tax debt, it's not always just about unpaid income taxes. There are different kinds of taxes that a deceased person might have owed, and understanding these can be quite helpful. Each type, you see, has its own implications for the estate and, potentially, for surviving family members.

One common type is unpaid income tax. This is money owed from past tax years where the deceased person either didn't file a return, or filed but didn't pay the full amount due. This is, perhaps, the most straightforward kind of tax debt to consider. The IRS will seek to collect this from the estate's assets, more or less, like any other debt.

Another type is estate tax. This is a tax on the right to transfer property at death. It's only applicable to very large estates, as there's a high exemption threshold. Most estates, honestly, don't owe federal estate tax. But if an estate does, this tax is paid from the estate's assets before distribution to heirs. It's a bit different from income tax, as it's specifically a tax on the transfer of wealth after death.

Other Potential Tax Obligations

Beyond income and estate taxes, there could be other tax obligations. For instance, if the deceased owned a business, there might be unpaid business taxes, like payroll taxes or self-employment taxes. These too would need to be settled by the estate. These can be particularly complex, as a matter of fact, and often require specialized knowledge.

Then there are gift taxes. If the deceased made large gifts during their lifetime that exceeded the annual exclusion amount and didn't pay the gift tax due, that liability could also fall to the estate. This is less common, but it's something to be aware of, you know, especially if the person was very generous with their wealth.

Property taxes, state income taxes, and local taxes are also potential debts. While these are not IRS debts, they are still debts that the estate must settle. The principles are somewhat similar: the estate's assets are used to pay these obligations before anything goes to beneficiaries. It's a comprehensive process, really, to ensure all financial loose ends are tied up.

The Role of the Estate in Paying Tax Debt

The estate is, essentially, the central player when it comes to settling a deceased person's tax debt. All of the person's assets become part of their estate. These assets are then used to pay off any outstanding debts, with the IRS typically being a priority creditor. This is how the system, you know, is set up to work.

The executor or personal representative is responsible for identifying all assets and liabilities of the estate. They must file a final income tax return for the deceased person for the year they passed away. They might also need to file an income tax return for the estate itself if it generates income during the probate process. These filings are critical steps in determining the total tax liability.

Once the tax liability is determined, the executor uses the estate's funds to pay it. This could involve liquidating assets, like selling property or investments, if there isn't enough cash on hand. The goal is to satisfy all creditors, including the IRS, before distributing anything to the heirs. It's a pretty clear order of operations, actually.

Order of Payments

When an estate has debts, there's a specific order in which they should be paid. This order is usually determined by state law, but federal debts, like those owed to the IRS, typically have priority. This means the IRS gets paid before most other creditors, and certainly before any beneficiaries receive their inheritance. This is, you know, a very important point for executors to remember.

Generally, the order might look something like this: administrative expenses of the estate (like court fees and attorney fees), then funeral expenses, then federal taxes, then state taxes, and then other creditors. This hierarchy ensures that the most critical obligations are met first. It's a system designed to bring order to what can be a very messy financial situation, in a way.

If the estate has sufficient assets, this process is usually smooth. The executor pays the IRS, gets a receipt, and moves on. However, if the assets are limited, the executor must strictly follow this payment order. Failing to do so could, arguably, lead to personal liability, as we discussed earlier. So, adhering to the rules is, basically, essential.

When an Estate is Insolvent

This is where the question of "forgiveness" really comes into play, in a manner of speaking. An estate is considered insolvent if its debts, including tax debts, are greater than its assets. In other words, there isn't enough money or property to pay everyone who is owed. This situation, frankly, can be very stressful for families.

If an estate is truly insolvent, and the executor has followed all the rules, prioritized payments correctly, and there's simply nothing left after paying higher-priority creditors, then the IRS generally cannot collect the remaining tax debt. They cannot pursue the deceased person's heirs for the debt, assuming those heirs did not receive assets improperly or were not otherwise personally liable. This is, you know, the closest thing to "forgiveness" you'll typically see.

It's crucial that the executor can demonstrate that the estate was, in fact, insolvent and that all available assets were used to pay debts in the correct order. This often requires detailed record-keeping and, sometimes, court oversight. Just saying the estate is insolvent isn't enough; you have to prove it. This is where, for instance, professional guidance can be incredibly valuable.

What Happens to Unpaid Debt in Insolvency?

When an estate is insolvent, the IRS will typically write off the remaining balance of the tax debt. They don't have a mechanism to collect from individuals who are not personally liable and who haven't received assets that should have gone to creditors. So, if the estate is properly administered and truly runs out of funds, the debt essentially becomes uncollectible. This is, actually, a relief for many families.

However, it's not quite "forgiveness" in the sense of the IRS actively wiping it clean. It's more like the debt becomes unrecoverable because there are no more assets to pursue. The IRS doesn't typically send a letter saying, "We forgive your loved one's debt." Instead, they simply close the case once they determine there are no more avenues for collection. This is, like, a practical outcome of the situation.

It's important to understand that this only applies to the deceased person's individual tax debt. If a surviving spouse was jointly liable for the debt, or if there were other circumstances that created personal liability for a family member, then that liability would persist. But for the deceased's individual obligations, insolvency of the estate is usually the end of the line for collection efforts.

Spousal Relief: A Potential Lifeline

Sometimes, a surviving spouse might be jointly liable for tax debt incurred during the marriage. This usually happens when a couple files a joint tax return. When a joint return is filed, both spouses are generally held responsible for the entire tax liability, even if one spouse earned all the income or was solely responsible for the tax issue. This can be a very difficult situation, obviously, for the surviving spouse.

However, the IRS offers something called "innocent spouse relief." This relief can free a spouse from responsibility for tax, interest, and penalties if their spouse (or former spouse) understated tax on a joint return and the innocent spouse didn't know about the understatement, and it would be unfair to hold them responsible. This is, essentially, a way for the IRS to provide a bit of fairness in certain situations.

There are three main types of spousal relief: innocent spouse relief, separation of liability relief, and equitable relief. Each has different criteria, and applying for them can be a bit complex. The surviving spouse would need to demonstrate that they meet the specific requirements for the type of relief they are seeking. It's a process that, frankly, requires careful attention to detail.

Applying for Spousal Relief

To apply for spousal relief, the surviving spouse typically needs to file Form 8857, Request for Innocent Spouse Relief. This form asks for detailed information about their situation, including why they believe they should not be held responsible for the tax debt. The IRS will review the request and make a determination based on the facts and circumstances. This is, you know, a formal process.

It's important to apply for this relief as soon as possible, as there are generally time limits for requesting it. For innocent spouse relief, for example, you usually have two years from the date the IRS first began collection activities against you. Missing these deadlines can make it much harder to get relief, so, basically, acting quickly is a good idea.

Even if the deceased spouse was the one who caused the tax problem, the surviving spouse might still be on the hook if they filed jointly. Spousal relief is designed to address those situations where it would be unfair to hold the surviving spouse liable. It's a really important option to explore if you find yourself in this kind of predicament, honestly.

Offers in Compromise (OIC) for Deceased Taxpayers

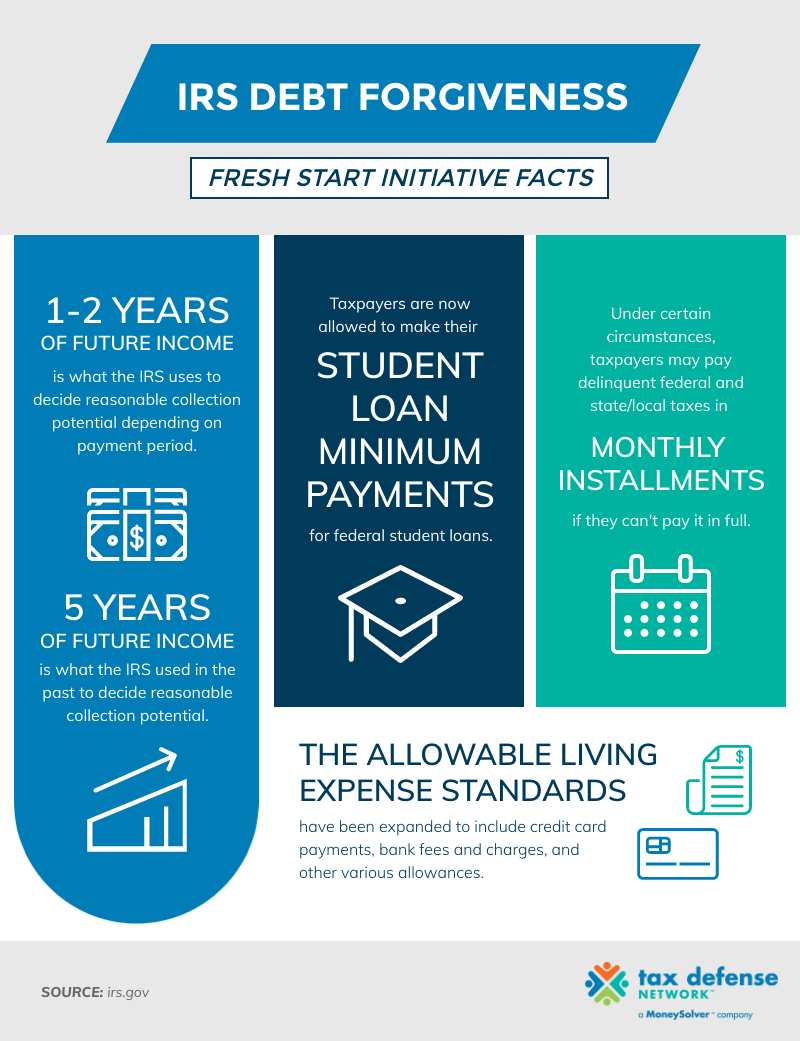

An Offer in Compromise (OIC) is an agreement between a taxpayer and the IRS that settles a tax liability for a lower amount than what is owed. The IRS might consider an OIC if there's doubt about the collectibility of the debt, meaning they believe they can't collect the full amount. This option, apparently, can be available even when the taxpayer has passed away.

If the deceased person's estate is struggling to pay the full tax debt, the executor or personal representative might be able to submit an OIC on behalf of the estate. The IRS will look at the estate's ability to pay, its assets, and its expenses. If it's clear that the estate cannot pay the full amount, an OIC might be accepted. This is, you know, a way to potentially reduce the overall burden.

However, getting an OIC accepted is not easy. The IRS scrutinizes these requests very carefully. They want to ensure they are getting the maximum amount they can reasonably expect to collect. The estate would need to provide detailed financial information to support the offer. It's a rather involved process, and there's no guarantee of acceptance, obviously.

When an OIC Might Be Considered

An OIC might be considered if the estate's assets are limited, and paying the full tax debt would cause undue hardship or leave the estate completely depleted. For example, if the only significant asset is a family home that would need to be sold, and the sale would leave the surviving family without a place to live, the IRS might be more inclined to consider an OIC. It's about, more or less, what is fair and practical.

The IRS will look at the "reasonable collection potential" of the estate. This includes the value of its assets, future income potential (if any, for the estate itself), and ability to pay. If the offer represents the most the IRS can expect to collect, considering the circumstances, then it might be approved. This is, basically, a negotiation, and the estate needs to present a strong case.

It's worth noting that if an OIC is accepted, the terms must be strictly adhered to. If the estate fails to meet the terms of the agreement, the OIC could be revoked, and the full original debt could become due again. So, it's a serious commitment, actually, once an offer is accepted.

Practical Steps for Executors and Family Members

If you're an executor or a family member dealing with a deceased person's financial affairs, taking the right steps can make a big difference. The first thing, honestly, is to not panic. While it can feel overwhelming, there are clear processes to follow. This is where, for example, a bit of organization can really help.

First, identify all assets and debts of the deceased. This includes bank accounts, investments, real estate, vehicles, and any outstanding bills or loans. You'll need to gather all relevant financial documents, including past tax returns. This comprehensive overview is, quite frankly, essential for understanding the full financial picture.

Next, determine if a final income tax return needs to be filed for the deceased. This is usually required for the year they passed away. Also, check if an estate income tax return (Form 1041) is necessary. These filings are crucial for establishing any final tax liability. This is, you know, a non-negotiable step.

Communicating with the IRS

It's a good idea to notify the IRS of the taxpayer's death. This can be done by sending a copy of the death certificate along with the final tax return. You should also include a letter explaining that the taxpayer is deceased. This helps the IRS update their records and ensures that future correspondence goes to the appropriate party, which is, basically, the executor.

If there's an existing tax debt, the executor should contact the IRS to discuss the situation. They can inquire about the balance due, payment options, and any potential relief programs. The IRS has procedures for dealing with deceased taxpayer accounts, and communicating openly can often lead to smoother resolutions. This is, you know, often the best approach.

Keep detailed records of all communications with the IRS, including dates, names of representatives, and summaries of conversations. This documentation can be invaluable if any questions arise later. Good record-keeping is, honestly, one of the most important things an executor can do.

Seeking Professional Help

Dealing with a deceased person's tax debt can be complex, especially if the estate is large, has many different types of assets, or if there are significant debts. This is where, apparently, professional help can be incredibly beneficial. Trying to figure it all out on your own can be a bit overwhelming, and frankly, unnecessary.

An estate attorney can guide the executor through the probate process, ensuring all legal requirements are met. They can help with understanding state laws regarding debt priority and asset distribution. Their expertise can prevent costly mistakes and, you know, provide a lot of peace of mind.

A tax professional, like a Certified Public Accountant (CPA) or an Enrolled Agent (EA), can help with preparing final tax returns for the deceased and the estate. They can also advise on any potential tax liabilities, explore options like spousal relief or Offers in Compromise, and represent the estate before the IRS. This specialized knowledge is, basically, invaluable.

Why Professional Guidance Matters

Professional guidance can help ensure that all tax obligations are handled correctly and efficiently. They can identify opportunities for reducing tax burdens or finding relief that you might not be aware of. They also help ensure compliance with all IRS rules, which can prevent future problems. This is, you know, a very smart investment for an executor.

Moreover, professionals can help navigate complex situations, such as an insolvent estate or disputes with creditors. Their experience can be particularly helpful in negotiating with the IRS or other debt collectors. It's like having a guide through a difficult path, which is, honestly, pretty comforting.

Ultimately, while the IRS doesn't just "forgive" tax debt from a deceased person, the debt is generally tied to the estate, not the family. With proper management and, perhaps, professional help, families can navigate this challenging time without inheriting the deceased's tax burden. Learn more about estate planning on our site, and for more specific tax questions, you can also refer to the IRS website on deceased taxpayers. This information, you know, comes from "My text" as a general reference for understanding how to approach complex topics.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does tax debt die with the person?

No, generally speaking, tax debt does not just disappear when a person passes away. The debt becomes an obligation of the deceased person's estate. The estate's assets are used to pay off these debts before any inheritance is distributed to heirs. So, in a way, the debt lives on, but it's tied to the assets, not directly to the family members themselves.

Who is responsible for a deceased person's tax debt?

The responsibility for a deceased person's tax debt primarily falls on their estate. The executor or personal representative of the estate is tasked with managing the estate's assets and paying off all valid debts, including taxes. Family members are typically not personally responsible for the debt unless specific circumstances apply, such as joint tax liabilities or if they improperly received assets from the estate.

Can the IRS collect from heirs?

In most cases, the IRS cannot directly collect a deceased person's tax debt from their heirs. The debt is collected from the deceased person's estate. However, if an heir improperly received assets from the estate before all debts, including taxes, were paid, the IRS might be able to pursue those specific assets from the heir. This is why, you know, it's so important for executors to follow the proper procedures for paying debts before distributing inheritances.

What Is the IRS Debt Forgiveness Program? - Tax Defense Network

Dealing With a Deceased's Tax Debts | Polston Tax

IRS Debt Forgiveness Program: Exploring Tax Relief Options